Not very, according to Greenpeace

Aug 25th 2006 |

DISPOSING of computers, monitors, printers and mobile phones is a large and growing environmental problem. Some 20m-50m tonnes of “e-waste” is produced each year, most of which ends up in the developing world. According to the European Union, e-waste is now the fastest-growing category. Last month new rules came into force in both Europe and California to oblige the industry to take responsibility for it. In Europe the Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) directive limits the use of many toxic materials in new electronic products sold in the European Union. In California mobile-phone retailers must now take back and recycle old phones.

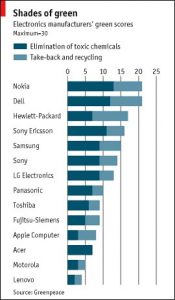

Many technology firms are already eliminating certain chemicals and offering recycling schemes to help their customers dispose of obsolete equipment. Yet there is a wide variation in just how green different companies are, according to Greenpeace, an environmental lobby group that launches a new e-waste campaign on August 25th. It has ranked the top mobile-phone and PC-makers based on their progress in eliminating chemicals and in taking back and recycling products (see chart).

The RoHS rules ban products containing any more than trace amounts of lead, mercury, cadmium and other hazardous substances, including some nasty materials called brominated flame-retardants (BFRs). To do well in Greenpeace’s rankings, firms must make sure both products and production processes are free of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and some BFRs that are not on the RoHS list. Greenpeace also wants companies to adopt a “precautionary principle” and avoid chemicals if their environmental impact is uncertain.

Although not everyone will agree with Greenpeace’s methodology, its ranking still has some merit. Nokia does well: the world’s biggest handset-maker has already got rid of PVC from its products and will eliminate all BFRs from next year (2007). But, Greenpeace grumbles, it is not sufficiently “precautionary” in other areas. Dell, however, scores well in this regard and on recycling, but loses marks for not having phased out PVC and BFRs yet, though it has set a deadline for doing so.

Perhaps the biggest surprise is the poor rating of Apple. Despite having an image steeped in California’s counterculture, it is one of the worst heel-draggers, says Zeina Al-Hajj of Greenpeace. The company insists that it has a strong record in recycling and has eliminated BFRs and PVC from the main plastic parts in its products. It scores badly because it has not eliminated such chemicals altogether, has not set time limits for doing so, does not provide a full list of regulated substances and is insufficiently precautionary for Greenpeace’s tastes. As for recycling, the 9,500 tonnes of electronics Apple says it has recycled since 1994 is puny given the amount of equipment the firm sells, says Ms Al-Hajj. Apple responds that many of its products (such as the iPod music-player) are small and light. Greenpeace points out that Nokia also makes tiny devices, but is much better at recycling them.

Alas for Apple, whatever the pros and cons of Greenpeace’s ranking criteria, consumers are likely to be influenced by it anyway. Comically, Greenpeace is now considering a plan to promote its e-waste campaign via podcasting—a technology that Apple helped to popularise.

This article appeared in the Business section of the print edition under the headline “How green is your Apple?” on The Economist.